Denim Ryder Review

Stone Wallace will become an institution to Western fans after they read this novel. A genre that has been virtually lost since the days of Louis L’Amour’s greatest literary work, Denim Ryder is filled with romance, intrigue and amazing depth. The bygone era of the old American West returns in Denim Ryder. It’s a pager turner that you won’t want to put down! – Tommy Lightfoot Garrett, Editor in Chief of Canyon Newspaper in Beverly Hills, and Contributing Editor of San Francisco News

It is not my nature to throw superlatives around when describing anything. This is especially true when it comes to today’s Western novels. Too often they are run of the mill at best. But after reading Denim Ryder I, a long-time Western writer myself, have to congratulate Stone Wallace for his literate style, plot structure and unique, sensitive characters in this truly original story. Well done, Mr. Wallace. This is one terrific read! —Steve Hayes, author of Gun for Revenge, Packing Iron, and A Coffin for Santa Rosa

Montana Dawn From Booklist

Montana Dawn has a life that is, if not idyllic, at least peaceful. She’s married to a kind man, and she’s putting her troubled childhood behind her. And then a gang of outlaws comes through her homestead, and, wouldn’t you know it, it turns out Montana had a pretty wide outlaw streak herself. Now Montana and Walt Egan, the gang leader, are in love and on the run, staying one small step ahead of the authorities. Montana, calling herself “Dawn” now, is having the best time of her life, but, as we all know, the best times don’t last forever. This unusual Western mines some fairly fresh ground: female outlaws are in relatively short supply, as are love stories about pairs of outlaws, but the author sells it completely. The characters are quite well drawn—villains who capture our interest and compassion—and the plot is engaging in a Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid kind of way: exciting but with a colorful, light feel to it—until the end. Recommend this one highly to Western readers. —David Pitt

Montana Dawn is a kind of western Bonnie Parker: when a charismatic outlaw rode through town one day, she saddled up. Female outlaws are in relatively short supply, but Wallace sells the premise completely. —Booklist Top 10 Westerns of the Decade

July 1, 2010

BEL AIR–Stone Wallace writes another winner. An Avalon Book this is really magnificently written. Wallace is one of the best storytellers on the planet today; he seems to grasp the western genre and is single-handedly reviving what many of us have missed for decades. “Montana Dawn” is a gripping story about a lady in the old west who is trying to lead a peaceful life only to have it destroyed when a band of outlaws arrive at her homestead in order to turn it and her life upside down. Turns out Montana has a way about her that no one reading it or the bad guys would expect.

Montana falls in love with Walt Egan, the gang leader, but don’t you think it ends there. That’s just when the excitement gets started. Stone is able to transform you back into the old west. You feel the gritty sand blowing in your eyes as the description of the surroundings are told to you. The reader also falls in love not only with Montana but even the bad guys. Why? Because Wallace knows how to build up characters and doesn’t make anyone just black or white. In life there is a lot of gray and he knows how to export that on to the written pages of this excellent story. That being said, there is absolutely nothing gray or mediocre about this author’s writing abilities. This story will jump off the page and on to your imagination, while making you want to relive the old west again.

When Montana and Walt decide to make a run for freedom, there is a lot more chasing them than the posse on their tails. It’s the reader’s fingers as the page-turner catapults you into a world that many of us thought was long gone. 231 pages of nonstop action and adventure is what you will be getting when you pick up this novel. I guarantee you won’t want to put it down until the last words are read.

“Montana Dawn” is available at Amazon and by going to the publisher’s website.

This book is a must-read for anyone who has ever enjoyed a western in their life. If you don’t like it, I will personally refund your money.

“Montana Dawn” is cut in the tradition of the very best of Louis L Amour. It is simply an amazing story packed with action, suspense and romance.

Tommy Lightfoot Garrett is a six time author, entertainment publicist, TV and Radio Host and Actor, along with being a journalist for Canyon News in Beverly Hills

Booklist

The Last Outlaw

Wallace, Stone (Author)

Aug 2011. 192 p. Avalon, hardcover, $23.95. (9780803476653).

Wallace follows up the splendid Montana Dawn (2010) with another fine western. It begins in a gritty Wyoming hotel room, where ex-con Cash McCall is contemplating the body of a woman sprawled on the floor. Then we jump back in time, as Cash recalls the day he was released from prison and the subsequent events that led to being in the hotel room. Cash is a well-designed character, a man who wants to turn his life around but who can’t seem to catch a break, winding up right back where he used to be, partnered up with a scoundrel and running from the law. As matters between Cash and his partner threaten to come to a violent conclusion, Cash seizes on a desperate plan to extricate himself. The story is definitely compelling, but it’s the risky, daring conclusion that will stay in the readers’ minds long after they’ve finished the book. The author takes a real chance here, but he pulls the ending off beautifully (and, it must be noted, dramatically). Keep a close watch on Wallace; he’s a writer with genuine and abundant talents.

— David Pitt

Booklist Online Review (9-1-2016)

This Five Star title published JULY 2016

Chance Gambel has a risky job: hunting down witnesses to crimes so they can help put accused criminals behind bars. It goes without saying that witnesses who don’t offer their testimony voluntarily probably don’t want to testify at all, so Chance often finds himself in dangerous situations, up against people who will go to great lengths not to be taken in. In this entertaining western, Chance partners up with a Mexican man, Francisco Velasquez, to find the outlaw who killed Francisco’s sister. As they doggedly pursue the wanted man, Chance keeps having a nagging doubt: Is Francisco his partner, or an enemy just biding his time until he can strike? The story is narrated by Chance, who starts out with a sort of seen-it-all attitude that turns to confusion and trepidation as his suspicions about Francisco’s true intentions begin to grow. Well plotted and skillfully written—no surprise from Stone Wallace, author of the excellent The Last Outlaw (2011) and Montana Dawn (2010). Western fans need to know about Wallace.

— David Pitt

Author Interviews

https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/our-communities/times/A-tale-to-give-you-the-chills-481932441.html

http://smdouglas.com/2017/02/22/exclusive-interview-author-stone-wallace/

Thursday, 24 July 2014

The Gentleman Gangster: Stone Wallace on George Raft – Part 1

In 1999 when the AFI released their 100 years…100 stars list of the top 50 greatest screen legends, most mainstream leading ladies and men were accounted for. They included Bogart – the dramatic actor, Cagney – the gangster, Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly – the musical stars, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and The Marx Brothers – the comedians and Kirk Douglas, Marlon Brando and Sydney Poitier – the new age. But I think every avid classic film fan has at least one or two objections to the list. For me I like to imagine George Raft has place 51. He was as accomplished an actor as Robinson or Bogart. He could dance as well as Astaire and Kelly and he was more alluringly handsome than James Dean, Gary Cooper and William Holden combined. However, due to a few career blunders and bad advice, Raft doesn’t have the enduring appeal that his talent and charm should have demanded. Another person who shares my view is Stone Wallace, film historian and author of George Raft: The Man Who Would be Bogart. He graciously gave me an interview on everything George Raft – his films, career and all the juicy facts about his much publicized personal life. Because there is so much information I decided to break the interview into two parts. Below is part 1, enjoy:

Emma: My all-time favorite film of Raft’s is Bolero as I think it shows his dramatic acting talents as well as dancing abilities. Do you have a favorite film of Rafts? Do you prefer him in a tough-guy gangster role or as a dancer?

Stone: I confess that I prefer George as a tough guy, and he excelled in such roles, especially visually. It was said that Raft patterned many of his on-camera hoodlums on gangsters he had known during his early New York days. But it’s also true that some real-life gangsters modeled themselves on George Raft. “Bugsy” Siegel tried to emulate Raft’s style of dress. “Crazy Joe” Gallo used to stand on the street corner flipping coins and talking out the side of his mouth. Despite his talents as an actor, George Raft had influence.

I first discovered George Raft watching him play against Cagney in Each Dawn I Die during a summer spent in Chicago where I whetted my appetite for all things vintage underworld, which since early boyhood has always been my passion. Raft’s “Hood” Stacey was an unforgettable screen character and I was immediately impressed by how Raft played (or effectively underplayed) the role and how much presence he had. He created the classic screen gangster: tough but ultimately courageous. Cagney himself admitted that Raft stole the picture from him. High praise indeed!

As for a favorite film: I enjoy all of his Warner Brothers output but I would have to give the nod to Invisible Stripes. Another great role for George: a sympathetic criminal. But the film also boasts a terrific supporting cast: Bogie, a young William Holden, and three favorite screen tough guys: Marc Lawrence, Paul Kelly and Joe Downing.

Emma: I read that Raft’s early life was spent with a number of ‘shady characters’ including some who would become key figures in the New York gangster underworld. What features of his upbringing do you think prevented him from entering a life of crime? Was it character or luck?

Stone: Raft said that the only two ways for a kid to survive Hell’s Kitchen was to become a criminal or succeed at sports. And in George’s case that pretty much held true since he never received much schooling. I don’t think he even finished grammar school. George, of course, was never truly a criminal. I’d say he remained on the outer fringes of the underworld. He did try sports: boxing and baseball, but was not very successful at either. Where he made his mark, of course, was as a dancer. And a dancer during those days in New York generally played at clubs that were associated with the underworld and so George rubbed shoulders with everyone from “Mad Dog” Coll to Dutch Schultz. His closest pal in the rackets, though, was a man whom George had basically grown up with who became one of New York’s top mobsters: Owney Madden. George willingly did “chores” for Madden because of their close friendship – primarily helping to run booze during those years of Prohibition. And later it was Madden who suggested that George should try his luck in the movies. Even bankrolling Raft until George got his “break” in pictures.

George did once say that he did hold youthful ambitions to become a big shot in the underworld but that he really didn’t have what it took and, more importantly, he didn’t want to disappoint his mother, whom he adored. In fact, she once caught George with a gun on his person and asked him not to come around the apartment again. This hurt George so much that he really tried to distance himself from participation in the rackets and put more effort into a career as a dancer – a vocation his mother heartily approved of.

Emma: Even after he became a Hollywood star, Raft was dogged by claims that he was involved in organized crime. He definitely seemed to have enduring friendships with several crime figures, do you think any of the suspicions were true?

Stone: It’s a gray area when it comes to his participating in any underworld activities after he became a movie star. Again, there have been rumors and Frances Dee, his co-star in Souls at Sea, once said: “Everyone knew that he (Raft) was a gangster,” though she never amplified her comment. But as for his friendship with crime figures: Certainly. Especially his open and publicized friendship with “Bugsy” Siegel. But in fairness, many other stars became friendly with Siegel, who apparently could be as charming as they come and a fine and generous companion. Heck, Jean Harlow was godmother to Siegel’s daughter Millicent. And a film figure as respected as Pat O’Brien could be found playing handball with Siegel. Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Gary Cooper – even studio head Jack L. Warner were seen in Siegel’s company. Unfortunately, because George did have a past association with the underworld and also because of his screen reputation, his association with Siegel hurt him more than it did other Hollywood celebrities. I think audiences of the day wanted to believe George Raft really was a gangster and palling around with a known mobster like The Bug solidified that reputation. What really sealed the deal, in my opinion, was when Raft, against orders from studio executives, went to bat for Siegel during the latter’s bookmaking trial. He testified on Siegel’s behalf and at one point risked a contempt of court charge because he became so vehement in his defense of Siegel that he completely disregarded court protocol. And there’s that famous photo of George and Siegel grinning at each other like Cheshire cats outside the courtroom that made front page headlines. What’s unfortunate is that Raft did not need negative publicity at this point in his career. He was starting the downward spiral in ’47.

Emma: Because of his background an underworld associations, did George Raft embrace or resent being cast as a movie tough guy?

Stone: I don’t think he objected to being a tough guy, provided his characters were on the side of good, such as in They Drive by Night and Manpower, where he played “men of the people.” Also later in his career where he played a succession of detectives and such. But I do feel that the gangster image might have hit a little too close to home. However, it did serve him well early in his career and certainly did make George Raft into a star. But once he reached that level of stardom where he could choose his roles (even at the risk of studio suspension – and by the way Raft holds the record at Paramount for the most time an actor was placed on suspension – 22 times in 7 years!) he clearly wanted to distance himself from playing hoods and racketeers, which is unfortunate because those decisions cost him roles in gems like Dead End and High Sierra.

Emma: He seemed to have a colorful young adulthood having stints as a dancer, chorus boy and an actor in vaudeville. How did Raft become interested in dancing? Is it true that he worked on some occasions with Rudolph Valentino?

Stone: Actually, Raft began his dancing career simply by hanging out at dance studios around New York. He possessed a natural ability and – like Cagney – had a knack for picking up dance routines quickly. He studied the moves of dancers of the day, perfected them to his own unique style, and was soon off and running. His mother was one of his earliest dance partners and they used to enter dance competitions together. George’s specialty was always the Charleston and whenever he performed that number it never failed to bring down the house. Unlike Cagney, whose dance moves were stiff and somewhat eccentric (and I don’t mean that in a bad way), George’s dancing was fluid and sinuous, almost snake-like. But both men tremendously admired each other’s dancing (and it should be noted that Fred Astaire was also a huge fan of Raft’s fancy footwork) and it was Cagney who personally recommended George for his dance contest rival in Taxi!

Yes, George and Valentino did work in New York tea rooms before Rudy made it big in the movies. Women (usually lonely, unattractive or elderly) would sip on cups of tea and study and then choose their dance companion – paying for the privilege, of course – and maybe even entice them into an after-hours rendezvous. Unfortunately, it was likely this experience that later was to tag George as a gigolo, a condemnation which he abhorred and vehemently denied. After Valentino died (and George remembered visiting with him shortly before his death and saw a very unhappy man), Raft was approached by theatrical producers to go on tour with some of Valentino’s former dancing partners – including an act with one of Valentino’s wives, Jean Acker, but Raft, to his credit, rejected all of these “ghoulish” propositions. Besides, he wanted to “make it” on his own merits, not capitalize off the fame of a deceased friend. But there was some logic in these offers as Raft possessed a striking resemblance to Rudy.

Emma: How did Raft get into film acting? Did he have any training before beginning acting or was he simply a natural performer?

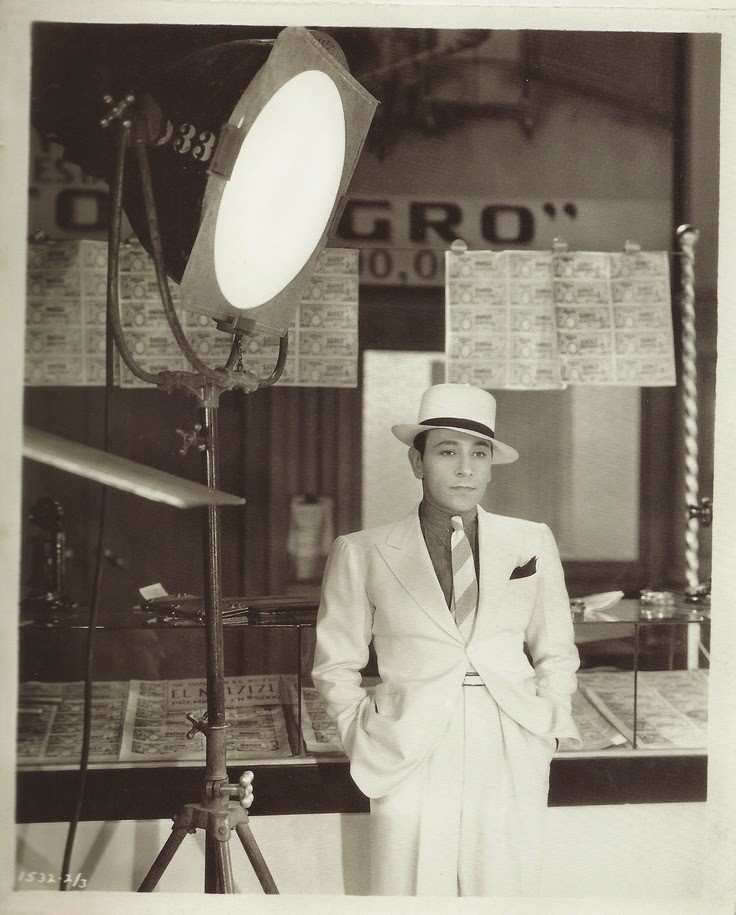

Stone: George was friendly with Texas Guinan, a famous cabaret hostess of the time and partner with mobster Larry Fay in the El Fey Club. (The pair were later immortalized, if somewhat fictionally, as Eddie Bartlett and Panama Smith in The Roaring Twenties, played respectively by James Cagney and Gladys George). George often danced at the club and when Texas was asked to go to Hollywood to appear in the movie Queen of the Night Clubs, George accompanied her – either as merely a companion or maybe her bodyguard. George appeared briefly in the movie. He initially was filmed doing a whirlwind dance number but the scene was cut for some reason and instead George can quickly be seen enthusiastically waving a baton while conducting a night club orchestra. George appeared in a few other minor film roles, such as Goldie and Side Street and eventually decided to try and make acting his career. The clubs in New York where George had earlier enjoyed success were rapidly closing down due to the Depression and George was anxious to try another line of work – one preferably related to show business. It took him a while and apparently he endured some rough times trying to establish himself, but he got his first break when director Rowland Brown ran into Raft at a prize fight and remembered George from his impressive dancing in vaudeville and cast him as Spencer Tracy’s second-in-command in the gangster drama Quick Millions. From there, George was off and running. His next “big” break came when Howard Hawks cast him as Paul Muni’s henchman inScarface. His success in that film led to his being placed under contract to Paramount.

Interesting about Scarface. Jack LaRue told me that it was he who was originally cast in the Guino Rinaldo role but that after just a few days’ filming director Hawks felt that LaRue possessed too much authority to be believable as Muni’s henchman. LaRue accepted the dismissal gracefully and even (supposedly) suggested his pal George Raft for the role. I tend not to believe this account. LaRue was just beginning his own career in movies and it seems unlikely an actor hungry for his own success would introduce his own competition. In any event, if true, Raft reciprocated the favor when he turned down The Story of Temple Drake and LaRue was given the role. Unfortunately, the results for Jack LaRue were much less favorable for his future career.

Emma: Would you say the Paramount years were the most successful for George Raft?

Stone: I’m really not a huge fan of most of Raft’s Paramount output. I think George fared much better at Warners and it’s interesting to speculate how his career would have progressed had he signed with Warners after the success of Scarface rather than going to Paramount. Paramount had a more European style whereas Warners of course was urban and gritty. But I will say that well into his Paramount contract George scored big with three features: The Glass Key, Souls at Sea and Spawn of the North (probably my second favourite Raft film). What is interesting is that Raft’s last film for the studio, The Lady’s from Kentucky, was relegated to the second feature on the double bill. Doesn’t really say much for George’s future with Paramount.

Emma: On a personal note, Raft had a short lived relationship with his only wife, Grayce Mulrooney, although they never legally separated. How did the pair meet and why did you think they never divorced?

Stone: Grayce Mulrooney had been one of George’s early ballroom partners, later to leave show business to work as a social worker, and while George dated many girls, Grayce held a particular attraction to George. While he wasn’t exactly keen on the idea of getting married and settling down given that he was focusing on advancing his career, he eventually gave in to her (persistent) demands that they marry and they wed in 1923 when George embarked on a four-month tour with on the Keith Vaudeville Circuit. The union was rocky right from the start and as far as Raft was concerned, his marriage to Grayce pretty much ended shortly after their honeymoon. Ironically, legally, because a divorce was never obtained, George Raft had one of Hollywood’s most lasting marriages: from 1923 until Grayce Mulrooney’s death in 1970. Forty-seven years. Incidentally, there’s a rumor that George actually had been married once before and that he had a son from that union. To my knowledge, it was something that – if true – George never discussed.

The reason Grayce gave for never divorcing George was because of her devout Catholicism. Raft believed her reasons were more selfish, that she felt it would be worth more financially to stay married to him than to merely accept a cut-and-dried divorce settlement. After all, she was receiving a hefty ten percent of his earnings and at his height George was averaging more than five grand a week.

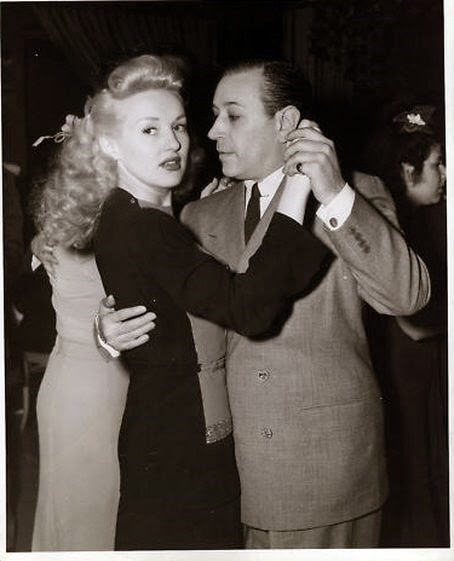

Emma: Raft notoriously had several extra-marital affairs; including apparently with famous actresses, such as, Norma Shearer, Betty Grable and Marlene Dietrich. Were any of these relationships serious? Was he seriously considering marrying any of them?

Stone: Another rumor was that George might not have really wanted a divorce from Grayce. Staying legally wed provided a convenient way for him ever to have to tie himself down in a relationship; allowed him to maintain his freedom. Raft always denied such was his intention. He said that he desperately wanted to marry socialite Virginia Pine and, later, Betty Grable, and had literally pleaded with Grayce on more than one occasion to divorce him. But she stubbornly refused. After his romance with Grable dissolved, Raft never allowed himself to get involved in a serious relationship and he dated primarily starlets (such as Barbara Payton) and hookers. It’s interesting to contemplate how Raft’s life would have fared had he ever been allowed the experience of marital life. If George sincerely did want to marry either Virginia Pine or Betty Grable, I think it’s sad that he was denied this happiness because of what I view as a greedy and maybe vindictive wife.

Raft’s relationship with Norma Shearer was another matter. Their coupling was frowned upon by MGM head Louis B. Mayer, who said: “A nice Jewish girl like Norma should not be going around with a roughneck like that.” Meaning Raft, of course. It is doubtful that their relationship ever would have led to marriage, however. They were merely steady dating companions; after all Norma hadn’t been widowed that long from Irving Thalberg, whom she deeply loved – as did L.B.

Marlene Dietrich and Carole Lombard were two gals Raft admits he was crazy about. While George and Carole occasionally dated, there could be no future for a lasting relationship with the shadow of Grayce Mulrooney always looming overhead. Carole also once made the comment that no girl could stand up to George Raft’s sexual needs. He had quite a reputation in that area, which I will tactfully refrain from elaborating on. Raft also apparently had a fling with Dietrich but a long term romantic relationship never developed between the two, though each deeply admired the other, personally and professionally. With all the turmoil that went on between Raft and Edward G. Robinson during the filming of Manpower, Dietrich wrote in her autobiography that she retained only the warmest memories of George Raft as her co-star in the movie.

Emma: Your book’s title clearly shows the connection between Raft’s and Humphrey Bogart’s careers. Raft is notorious for turning down the starring roles in what would become famous Bogart pictures, such as High Sierra and The Maltese Falcon. Do you think Raft could have executed these roles as well as Bogart? Also, do you see other similarities between the men, such as, acting styles?

Stone: I think Raft would have done very well as urban gangster and former street kid “Baby Face” Martin in Dead End. After all, that was Raft’s milieu, unlike Bogie who was born into privilege (if not a particularly happy home life). I’m not as sure about High Sierra. Bogart had already played a grassroots bandit in The Petrified Forest, whereas, again, Raft was more closely associated with the suave, well-dressed “night club”-type of racketeer. It’s kind of like trying to picture George Raft as a cowboy, which I don’t think ever would have come off. As for The Maltese Falcon, the picture certainly would have been different with Raft essaying the role of Sam Spade . . . but arguably it could have worked because of John Huston’s expert direction. If Raft behaved himself on the set I think Huston could have coaxed an effective performance out of him. Would it have been as good a film as the version we now have? Probably not. The movie has a terrific ensemble cast and the players work in a near-perfect synchronicity, like the finest tuned clockwork. I feel that Raft might have somehow upset that balance. I do know that Huston adamantly did not want to work with Raft, whom he did not particularly care for as an actor or as a person, once referring to him as a “definite Mafia type.” Huston expected there to be trouble on the set based on Raft’s reputation – and besides he had Bogart in mind for the part all along.

Of course the story about Raft turning down Casablanca is false, even though in later years Raft himself perpetuated the story (like Bela Lugosi later claiming it was he who persuaded Universal to cast Boris Karloff as the monster in Frankenstein). The truth is that Raft actually campaigned for the role of Rick, and Jack Warner was okay to cast him, but Hal Wallis and Michael Curtiz wanted Bogart. Wallis, in particular, had grown dissatisfied with how George thought he could dictate solely what was right or wrong for him when it came to projects. Had Raft taken on The Maltese Falcon, then it is possible he might have been awarded Casablanca, but thanks to George’s career blunders at the studio, Bogart had risen rapidly through the ranks and was no longer regarded as “George Raft’s brother-in-law.”

Emma: What do you feel was George’s main strength as an actor?

Stone: I’ve always said that George Raft performed at his best when paired with a strong (usually male) co-star. The proof is in the pudding: Consider Quick Millions (Spencer Tracy), Scarface (Paul Muni), The Bowery (Wallace Beery), Souls at Sea (Gary Cooper), Spawn of the North (Henry Fonda), Each Dawn I Die (Cagney), Invisible Stripes and They Drive by Night (Bogart), Manpower (Edward G. Robinson) – up until Rogue Cop (Robert Taylor). And of course, talented directors like Howard Hawks, Henry Hathaway, Lloyd Bacon, Raoul Walsh, Billy Wilder. Since I know you are an admirer of Bolero, I will also concede having a co-star like Carole Lombard definitely didn’t hurt. But if you look at when Raft’s career began to fade, you’ll notice the (lack of) calibre of his co-star and directors not particular of the highest talent.

Emma: Raft probably does not have the legend status nor the enduring appeal today of Bogart. However, the stereotype of the film ‘gangster’ was created by him along with a handful of others. Why do you think Raft is not remembered today in a similar way to Bogart or Cagney?

Stone: Simply, bad career choices. A determined stubbornness not to be typecast as a gangster or hoodlum and, to a lesser extent, his desire not to die on-camera. It is obvious that Raft took his decision over accepting film roles seriously. He once said he wanted the public to like him (which I feel demonstrates his innate insecurity) and that was why he turned down the gangster roles in The Story of Temple Drake and Dead End. He found the role of “Trigger” in the former repulsive and sincerely worried that if he took on the part audiences would think he, George Raft, was like the character and that his future as an actor would be finished. Jack LaRue took on the role and it’s true that his career never really took off afterward. So George’s argument actually might have been valid. He rejected Dead End because he did not want the character of “Baby Face” Martin to encourage the kids in the film to partake of a life of crime, and of course that would have negated the whole point of the story. Later, of course, came the famous Warner Brothers rejections. What’s really ironic and makes one question George Raft’s thinking is why he would turn down the part of sympathetic gangster Roy Earle in High Sierra, a big-budget movie based on a bestselling novel by a recognized writer, and virtually beg to go on loan-out to United Artists to appear as a gangster (who dies at the end) in a much lesser – and silly – production: The House Across the Bay? A box of cigars to anyone who can figure out the reasoning behind that decision. I think what also really hurt George’s career was his insistence after leaving the gates of Warner Brothers to play mainly good guys. The roles, in smaller budget movies at lesser studios, very soon became monotonous for audiences. In fact, when Billy Wilder approached Raft about playing the opportunistic insurance agent Walter Neff in Double Indemnity, Raft insisted on knowing when Neff was going to flash open his badge to reveal to Barbara Stanwyck that he was really an undercover cop. So much for George Raft in the part. In the 50s George Raft’s “star” shone twice more – though briefly. And both times it was with him playing a gangster: Rogue Cop and Some Like It Hot. On the set of the latter Raft was quoted as saying: “Typecasting again. But what can you do about it? I just never seemed to get the breaks that Bogart and Cagney did.”

The truth is, Raft was afforded virtually all of the breaks. He just never took advantage of them. John Huston said of Raft during the time George was under contract at Warners: “Everything at the studio was intended for George Raft.” From The Sea Wolf to The Maltese Falcon, these were good parts that George missed out on. His beneficiaries in these roles became legends while Raft in the years to come became nearly a forgotten name.

Here’s an enlightening story: A friend of mine appeared as an extra in the movie What Price Glory? and one day overheard James Cagney speaking with his co-star Dan Dailey. Cagney was saying that George Raft could have been one of the biggest stars in Hollywood if he’d only used better judgment. Raft would in later years place much of the blame on bad advice given him by his agent. But I don’t quite buy it. Raft was a fiercely independent personality and was perfectly capable of making his own choices. Just too bad that many of them were bad.

Emma: Out of all the Hollywood figures in Hollywood, why did you choose Raft to be the focus of your biography?

Stone: Because I think George Raft is one of the most fascinating show business personalities, yet, career missteps aside, he has never really received his due. Today he’s nowhere near as known as many of his movie contemporaries. He may not have been a great actor, but as I said before, he had a tremendous presence that even the most jaded critic would have to say was hard to turn attention away from. The guy was watchable. It is interesting how the program Biography did stories on Bogie, Cagney, Eddie Robinson and even John Garfield, yet Raft, who led the most colorful life of all, was never featured, and I even wrote to A&E to request they do a program on Raft. I mean from his days as a tough kid surviving Hell’s Kitchen, his lifelong association with the underworld, top Hollywood stardom, then his career nosedive due to his turning down roles in films that became enduring Hollywood classics. His experience in Cuba during the Castro Revolution and his later expulsion from England. And of course his Don Juan reputation with famous and beautiful women of the day – and that is an article in itself.

To quote Bogie as Sam Spade in the famous role that George Raft turned down: “The stuff dreams are made of.”

I don’t think I can end this article better than that other than to say a big thank you to Stone Wallace for answering my questions. Also for anyone interesting in the career and personal life of George Raft, check out Stone’s book: George Raft: The Man Who Would be Bogart.